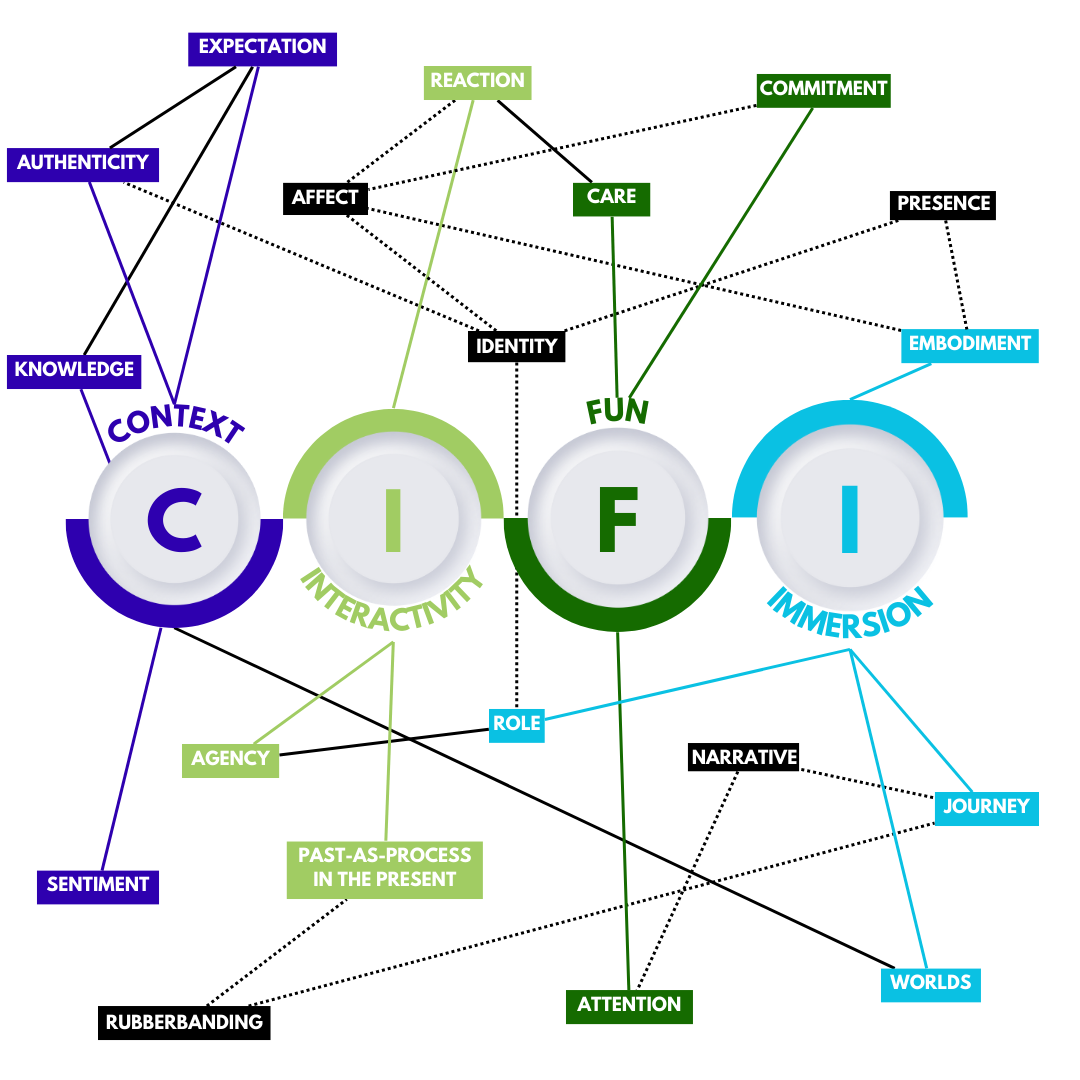

Context

Context is part of what informs the way these games are designed, played, and thought about. It has to do with the accuracy of historical settings or details, whether a game is seen as an authentic depiction of the past, the expectations players and developers have about past-play, and the role of knowledge (things the player comes in knowing, as well as things the player learns by playing) in historical video games.

Authenticity

Past-play often involves games that aim to recreate or evoke real-life events, cultures, settings, and people from history. Authenticity is the quality of how “real” a game’s portrayal of these elements of the past is, whether from the perspective of a developer, player, or steward of the past. Authenticity can have a lot to do with how accurate a game purports to be, but it can also relate to popular understandings about a setting, culture, or time, that may not actually be based in fact.

Expectation

If players expect certain things about what a historical video game looks like, how they are supposed to play it, and who or what it will depict, games that do or don’t align with those expectations can spur different reactions from players. If designers have certain expectations about what a historical video game looks like, that can limit the kinds of historical game design we see in the industry.

Knowledge

Knowledge refers to those facts, opinions, and understandings learned through play, as well as those facts, opinions and understandings a player possesses or draws from other sources prior to play. This concept also refers to the knowledge drawn from historical (and non-historical) sources by developers and designers when constructing a historical video game.

Sentiment

Sentiment, like Authenticity, is a discursively informed measure of societal attitudes towards historical events. These attitudes align with hegemonic understandings of past events and time periods, and influence historical representations in games and other media. Culturally and societally perpetuated ideas about whether an event or period “should” or “should not” be rendered playable, as well as the degree to which developers and players go along with or push up against these ideas–sentiments–impacts what stories are told in historical video games, by whom, and to what end.

Interactivity

Interactivity is one of the core defining elements that sets video games apart from other media. In order to play a game, a player has to deliver input and participate in the created environment. Through interaction, players can challenge, discuss, experience and get a deeper understanding of the game world and the history that is presented to them. It is also expressed in how a player responds to things that happen in a game, and how a game responds to the input of the player.

Agency

Agency dictates the degree to which a player is able to interact with the game world. Some games give players fewer possibilities in a story or the game world itself, often in order to tell a specific narrative or convey a certain idea. Other games may offer the player a lot more freedom and options to interact with the world around them. The player gets an array of choices that can affect the story they tell–and how much they feel like they get to tell it.

Past-as-Process in the Present

Our ideas and conceptions about the past change constantly, which can even be distilled by looking at video games. This is not the only change reflected in this media. Our own society changes all the time and these trends make their way into all media.

Reaction

A player’s Reaction to game stimuli–be that story beats, game objects, or recreations of historical events or settings–makes up a large part of how they engage with the game. While Agency refers to interaction, Reaction refers to actions that a player can take outside of the game (such as swearing or removing a headset in response to a fail condition), physiological responses, and the degree to which a player is affected by a given stimulus.

Fun

Fun is a word that almost everyone will be familiar with and hopefully uses on a daily basis. This also makes it harder to pin down. Fun is the moment of enjoyment, often associated with leisure activities and thus all types of games. In A Theory of Fun for Game Design Koster defines it as ‘the act of mastering a problem mentally’, something that video games offer plentiful. Fun, of course, is highly subjective. Some players might enjoy challenges, others might enjoy surprises, and still others might experience a feeling of wonder or a sweeping story and identify that as the source of their fun. The games that are ‘fun’ make us come back to them or give them meaning.

Attention

Attention in historical video games is a key ingredient that enables players to become active participants in the exploration and understanding of history. It can manifest through captivating visuals, compelling storylines and, of course, the ability to interact with the world around the player and the people in it. Game creators can employ all types of visual or audio cues to guide a player’s attention to something and to persuade them to continue interacting with their creation. These games create opportunities for players to delve into the past and the desire to unravel historical mysteries. As researchers, we are concerned with what different types of past-players attend to during play, and what sorts of elements influence this attention.

Care

Care and commitment are closely related. Because we care about the game or what is in it, we are willing to make commitments. But why do we care? This can have more than one reason, and will be different for each player. One way to make a player care is by telling a compelling story or by introducing captivating characters the player gets invested in.

Commitment

Part of the fun of video games also comes from the sense of commitment they are able to instill in players. This can be in a quite practical way–think of all the hours you’ve spent on your favorite game–but it can also be in more abstract ways. Some players might feel commitment because of certain narrative elements or NPCs and want to do well. Others might be committed to overcome a certain obstacle or tackle a problem and are willing to not only spend time in the game to hone their skills, but also outside of it. They might be willing to look up solutions on Youtube or hunt fora for answers. For historical games, players might look up more on the past represented in the game in order to improve or simply because the game got them enthusiastic.

Immersion

Immersion is a term to describe how people can be captivated and submerged in the digital world that is presented to them in video games. For a moment they feel as if they are part of the game world, feel like they are one with the character, or, in the case of historical video games, momentarily transported to the past. This can be achieved by a range of different elements such as environment, architecture, clothing, language, customs, sounds, storytelling and visuals. Players then get to interact with the constructed historical environments and explore them.

Embodiment

Embodiment refers to the physiological phenomenon of feeling as though one is their character, or that their own actions are their character’s actions. The process of embodiment renders players into actors, experiencing and making history as they play; historying. Embodiment also has to do with Affect in that players often Embody their characters’ emotions while playing, or feel that their Identity bleeds across the lines of game-world and real-world.

Journey

Throughout a video game, a story might be told by the game creators. Or when no set narrative is present, as might be the case in grand strategy games, players may think of stories themselves. By playing a game, things start developing. A character might level up, a new challenge may arise or perhaps a mystery is finally solved. The time spent in the game and the subsequent results of interacting with it are the indicators of a journey. Journeys are not just physical ones, but rather a whole process of getting from point A to point B.

Role

Players don’t just get agency in video games, they also get to be someone, they take on a role in the world that is surrounding them. In games such as Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla this is in a more literal sense. The player is interacting with the world as Eivor, hearing their voice, looking through their eyes and completing quests that will advance towards the goals that matter to Eivor. For other types of games, the role might be less defined. Take grand strategy games. In these types of games the player is more of a god, looking down on a map. The role in this case might vary more from player to player, Perhaps you see yourself in the role of a cruel tyrant or perhaps a merciful god. The chosen role can dictate some of the choices that you make in a game, sculpting your own role.

Worlds

Within games, players move around in a space designed by the game creators. These can be small or large, but are always limited in some sense. The worlds can also consist of a series of levels, grouped together on artistic, thematic or spatial grounds. When talking about historical video games, players can be transported to any past and explore the world that was created. Through audio, visual or textual elements, the past world is introduced to the player, who then gets to interact with it.

Resonance

Affect

A term borrowed from sociology and psychology, affect refers to the emotional processes that a game elicits (intentionally or not) in the player. Affect can cause things like bleed–a player being impacted by their character’s emotional state, or vice versa–and as an important factor in the degree to which players feel as though they are their character (Embodiment), as well as the extent to which they commit to the world and rules of the game they are playing.

Identity

Identity has to do with who you are. Yes, you! When a player chooses to play a game, they bring parts of themselves into the game. Likewise, playing a game might allow a player to take part of the game with them after they’ve played. This can encompass skills, quirks, or catchphrases, but Identity in CIFI also has to do with if and how a player feels changed by the game. Who are they before and after past-play? Identity also is relevant to questions of representation; what kinds of players play historical games? What kinds of perspectivizing characters exist in these worlds? What range of identities are playable, watchable, available to interact with in historical video games?

Narrative

Narrative refers to the story told through playing a game. No two players will play the same game in the exact same way, even if the story coded into the game’s design is linear and unchangeable. Better yet, the majority of historical video games don’t just have one singular storytelling path. The narrative of a video game has implications for what stories are and aren’t told in historical settings, how the type of narrative–length, format, content, presentation–in a game can influence a player’s experience of said game, and the role of narrative construction in designing a “fun” game.

Presence

Presence, also known as Telepresence, is a term for the phenomenon of feeling as though one is physically in the game setting. Relating to Immersion and Affect, the degree of Presence a player feels can be influenced by their emotional connection to a character, processes of self-involvement, various immersive and immersion-breaking elements of the assemblage of play, and a player’s willingness (or lack thereof) to “lose themselves” in a game experience.

Rubberbanding

Rubberbanding is the process of experientially snapping between past and present during past-play. Related to Journeying and the notion of past as a process enacted by players and game creators in the present, this notion of rubberbanding is what actually makes historical video games feel like time machines.