Figure 1: How main subject, DEV-lenses, subprojects, and case-studies fit together.

Playful Time Machines

Extended Project Description

NB the text below is a slightly edited excerpt of the original proposal submitted to the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) VIDI programme. If you're interested in the full proposal, reach out to the project lead: Angus Mol a.a.a.mol[at]hum.leidenuniv.nl

Introduction

In video games, the past is present. Games let us rule like Cleopatra, fight as unnamed soldiers in the muddy battlefields of the ‘Great War’, or raid like a Viking. These examples, taken from recent titles Sid Meier’s Civilization VI (‘Civ’), Battlefield 1, and Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla, are just a tiny fraction of the vast array of past experiences offered to the more than two billion people who play games. While gaming is still considered by some as ‘simply’ a pastime, the impact games have on our relation to past times should not be underestimated. For example, Civ, a game that takes its players on a tour of history that spans the “Stone Age to the Information Age”, was played for more than 1.2 billion hours from 2010 to 2016 — dwarfing time spent in the same period in any of the world’s best visited museums (Mol et al. 2017a). The Playful Time Machines project (PlayTime) will provide an original, comprehensive, and urgently needed view of how video games are reshaping our relationship with the past in a way that is as fascinatingly complex as it is popular. My team and I will do so by pioneering an interdisciplinary approach that allows us to investigate the mechanic, dynamic, and aesthetic components of our play with the past in depth.

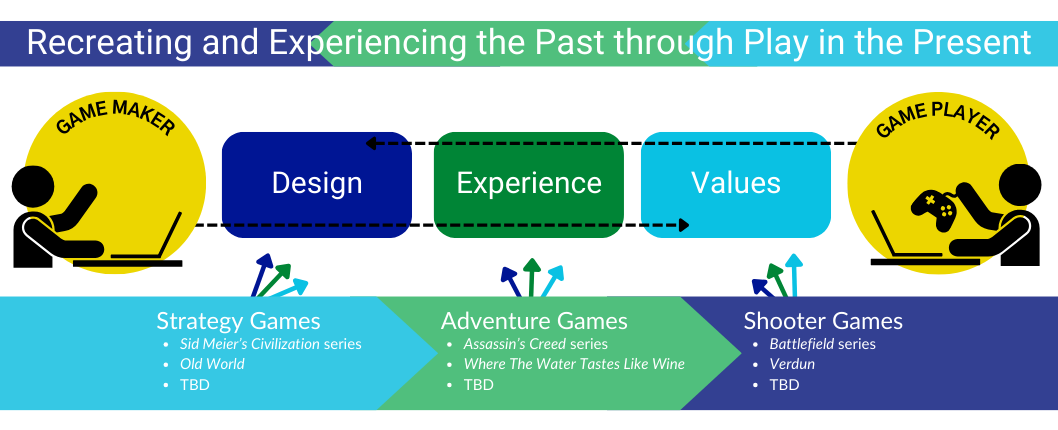

The idea of games as time machines in which you can leave the ‘here and now’ behind — playing on Huizinga (1938)’s concept of games as spatiotemporally set-aside ‘magic circles’ — goes far beyond paradoxical metaphor (Graham 2020). In games, past and present are caught up in a ‘recursive loop’ of game design, computer-powered play, and personal and collective conceptions of the past (Figure 1). These immersive experiences affect our personal sense of histories and heritage and, at larger levels, this impacts heritage-making and memorialization in our societies (Champion 2010; Mol 2020; Pfister and Zimmermann 2020). At the same time, the things we experience through play are constructed from the contemporary ideas, concerns, and sensibilities held by game makers and players about the past. In short, video games are both shaped by and reforge our contemporary experience of the past. PlayTime will investigate this recursive process of past-play and the effects it has on us by establishing a new and foundational framework for its study.

|

Using an interdisciplinary approach PlayTime asks…

PlayTime will synthesize answers to these questions, by connecting three subprojects on the Design, Experience, and Values of past-play in Strategy, Adventure, and (First-Person-)Shooter games, with the aim to:

|

To understand their broader relevance, PlayTime will study how games work simultaneously as “rules, play, and culture” (Carr 2007; Salen and Zimmerman 2004: 102). Games are rule-driven artefacts (created by makers and adhered to by players), but also instill their own cultural rules through past-play. This quality can be, but is certainly not always beneficial for personal and societal understandings of the past or present. For example, during the mind-boggling number of hours players have been immersed in Civ, the game gives them experiences critiqued as prioritizing Western cultural values above others, with gameplay rooted in Colonialism (Lammes 2005; Loban and Apperley 2019; Mol et al. 2017a). In studying games as persuasive, culturally produced experiences, PlayTime reinforces the scientific and societal value of the emerging body of research on past-play (Mol et al. 2017b), contributes new elements to heritage, historical, and other humanities fields studying the role of the past in the digital present (e.g. Champion 2020; Graham 2020; Morgan 2019; Reinhard 2018, Wright 2018), and joins scholarship elucidating the entanglements of video games with culture and society at large (e.g. Apperley 2010; Dyer-Witheford and dePeuter 2009; Lammes et al. 2019).

The past and play each represent highly affective and engaging subjects, and their combination in past-play has enormous potential to positively affect society. PlayTime will directly contribute to this. In fact, the design of this research project rests greatly on my interest and innovation in Open Science and Science Communication. This, and my network straddling the game community and industry and heritage field, means PlayTime will gather and share actionable insights in direct interactions with citizen players, game makers, and ‘stewards of the past’.

Citizen Players

Compared to most other media providing access to the past, games have an enormous reach. What is more, these persuasive experiences directly shape our views on the past — e.g. a recent survey I undertook showed that 90% of respondents (n=1676) believed that video games can change a person’s viewpoint on a historical event. Whether you agree with this development or not, video games have tremendous potential, both in a quantitative and qualitative sense, to shape our engagement with the past. In direct interactions, PlayTime will build on a shared passion for games to enter into conversations with citizen players about how we deal with the past in the present, including but not limited to discussions on the heritages of war and colonialism.

PlayTime will reach out to citizens, and particularly citizen players interested in the past, with:

- A project website with a section aimed specifically at citizen players, featuring game reviews, news, and popular scientific videos (a VALUE website of which I am editor in chief currently draws 3000 page views/month)

- PlayTime will organize and sponsor two game jams (creative contests in which participants make prototype games). Proto-type games made will be available for download and playable during an exhibit at Leiden University (a similar event VALUE organized drew nearly 2.000 visitors in one month).

- Weekly live-streams on Twitch will provide a direct means to converse with citizens about games and the past, as well as share project insights about how such past-play works (my current live-streaming activities have reached more than 25.000 viewers globally).

- PlayTime will share results in (inter)national news media and game journalism outlets, such as Kotaku or Eurogamer (my recent outputs in national news media such as nl and Volkskrant have reached 2-3 million people).

Game Makers

The making of games is a 200-billion-dollar annual business. When it comes to the potential for innovation, most bigger companies prefer to ‘play it safe’, letting market research and still predominantly white, male executives lead game development. One result of this is that video games end up re-telling conservative and Western ‘grand narratives’, often in a terribly persuasive way (see e.g. Lammes 2005; Loban and Apperley 2019; Mol et al. 2017a). Bigger companies are only slowly coming to terms with the fact that their games are as much entertainment products as they are institutions shaping and shaped by the cultural politics of past and present (Mol 2020). Fortunately, smaller game studios and independent creators are already active to create commercially viable games that are also diverse and knowledge-driven forms of engagement with the past.

PlayTime seeks to contribute to their forward-thinking, bottom-up initiative in a number of ways:

- PlayTime’s advisory board contains three indie game developers. Knowledge will not only be shared between these game makers and project members, but through their professional networks PlayTime will directly reach others looking for research-driven innovations on past-play.

- The jams (see above) will be open to all, but explicitly target Dutch game development students and brings these together with ‘stewards of the past’ (see below).

- We will publish a white paper for the game industry, highlighting project results and including actionable recommendations for more diverse and inclusive games based on the past.

- Project results will not only be presented at academic venues, but also at game development events, such as Games for Good and the Game Developer Conference.

Stewards of the Past

Since the 1964 Sumerian Game experiment, ‘stewards of the past’ (local and national heritage organizations, such as museums and archives, as well as individual scholars, educators and other professionals who see it as their primary role to care for and provide access to the past) have understood that computers hold the key to tell evocative histories of local and global heritages (Champion 2010). Especially in the last decade there has been a growing interest in video games by museums, educators, scholars and others. However, based on my experience working with Dutch, German, Belgium, and British heritage organizations through VALUE, it is clear that stewards of the past would like to tap into this potential of digital play but have trouble figuring out by themselves how this entertainment medium fits their primary mission. In short, expertise on video games is missing in this field, connections are missing between these organizations and the game industry, and resources are lacking to develop these things.

PlayTime seeks to bring the results of its research directly to this stakeholder group in the following ways:

- PlayTime’s advisory board contains two heritage experts, who will advise on and monitor PlayTime impact and further augment access to stakeholder networks.

- In the game jams (see above), stewards of the past will collaborate with young game makers.

- We will publish a white paper for stewards of the past, highlighting project results and including actionable recommendations on how to incorporate games in knowledge-driven activities.

- Project results will not only be presented at academic venues, but also with the (inter)national heritage sector, such as at de Reuvensdagen and ICOMOS events.

Summary

Increasingly, people experience the past not through textbooks, museum visits, or even television, but through video games. To anyone who has played or seen someone playing any of the thousands of popular games set in the past, it is clear that these ‘playful time machines’ have enormous impact on how we relate to the past in the present. Yet, for a phenomenon that is as fascinating as it is rich and popular, it is surprising how little we still know of how past-play works in practice.

The Playful Time Machines project (PlayTime) undertakes the first comprehensive study of the way video games are reshaping our relationship with the past. Through a new combination of qualitative and quantitative, interdisciplinary methods, the team will investigate the ways we re-create and experience the past through play. This is done in three subprojects covering nine case-studies of contemporary strategy, adventure, and shooter games. Using ontologies and game development theory, PlayTime shows how past-play is expressed through game rules and design. Games user research will be employed in controlled settings to study past-play as it happens. The project also answers how game players and makers mediate and re-create their views on and values of the past from the perspective of game and heritage studies and by studying large bodies of (para)texts with Digital Humanities tools. Through its innovation in concept, method, and data, PlayTime will (1) anchor an emerging body of research at the intersections of past and play in game studies, while retaining connections to disciplines studying the past; (2) provide an interdisciplinary framework for the study of the past in interactive, digital media and; (3) share actionable knowledge with citizen players, game makers, and ‘stewards of the past’ and take practical actions with an aim to understand, enrich, and diversify these playful time machines.

Full Description

A Common Framework

Part of the solution resides in creating opportunities for cross-disciplinary communication, between academics as well as between game makers and ‘stewards of the past’ (see 2b). Another key development is to create common conceptual and methodological frameworks, particularly those that establish direct connections with disciplines studying the past and those studying games and play.

PlayTime will do this by drawing on an established model for thinking about games: the Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics or MDA-model (Hunicke et al. 2004; see Figure 1 & Approach). To study past-play, this MDA-model will be significantly expanded and updated with state-of-the-art Digital Humanities and game analytic tools as well as methods from heritage and game studies, resulting in a new iteration of the MDA-model: the Design, Experience, and Values framework, or DEV for short. PlayTime widens current mono-disciplinal perspectives and conceptualizes past-play as a fundamental affective and value-driven experience and way of knowing the past. This broader view is rooted in a rich humanistic tradition of study into aesthetics, phenomenology, and epistemology (e.g. Ryan 2001; Sharp and Thomas 2019; Shelley 2017; Smith 2018) and contributes to current thinking about the role of popular media in cultural memory and the impact of subjective, immersive, and emotive digital technologies (e.g. Boler and Davis 2020; Holtorf 2010; Hoskins 2018; Isbister 2016; Katifori et al. 2018; Pfister and Zimmermann 2020).

The subjective, experiential, and dynamic quality of past-play gives rise to major methodological and conceptual challenges, which boil down to one issue: how to study experiences of the past in and through play by others than ourselves? The majority of current studies are based on a single player’s experience: the researcher. Such expert views and this approach are valuable in understanding the form and depth of past-play, but cannot operate at a scale that does justice to the breadth of player backgrounds and the experiences offered to them in games. In addition, it is of critical importance to better understand the role of game development on past-play (Copplestone 2017). PlayTime shifts the focus from the views of individual academic ‘critics’ to a more open and co-creative view of past-play using a formal (i.e. replicable and extendable), multi-perspective (of game makers and players), multi-scalar (i.e. based on individual experiences and large player groups), and qualitative and quantitative data-driven approach.

Approach

PlayTime builds and significantly innovates on the MDA-model, “a formal approach to understanding games, one which attempts to bridge the gap between game design and development, game criticism, and technical game research” (Hunicke et al. 2004). Following this model, games consist of Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetic components which together create compelling and affective experiences. Game makers design mechanics: they write game rules as computer code and produce the digital assets (models, texts, sounds, etc.) that shape how play should take place during the game. Players do not passively consume output, but co-create the experience of play. This results from their own input in an embodied (presence in-game, but also physical bodily actions; Keogh 2018) and aesthetic sense. In PlayTime, ‘aesthetics’ refers to the ways players value the past and understand the sensory and emotional characteristics of game-based experiences of the past, as well as how players and makers express coherent statements of opinion, belief, or attitude toward the underlying principles of play with the past (Munslow 2019; Sharp and Thomas 2019; McCall 2020).

In PlayTime, the updated DEV-model provides three similar and specific lenses into past-play: mechanics for the design of the past in games, dynamics for what happens in the moment of past-play, and aesthetics for understanding how players consume and co-create the past in games (Figure 1). In PlayTime each lens is the focus of its own subproject, each bringing new concepts and tools to the study of past-play and yielding detailed insights and outputs, but working in synthesis to provide a deeper understanding of how we re-create and experience the past in the present through play. To reinforce the coherence of its three-pronged approach, all projects will (1) draw on the conceptual framework discussed above, (2) limit their scope to a diverse and large but defined group of players from Western Europe and games in the English language that are popular there, and (3) will be based on comparative research on nine case-study games (Figure 1, bottom).

Preparatory work

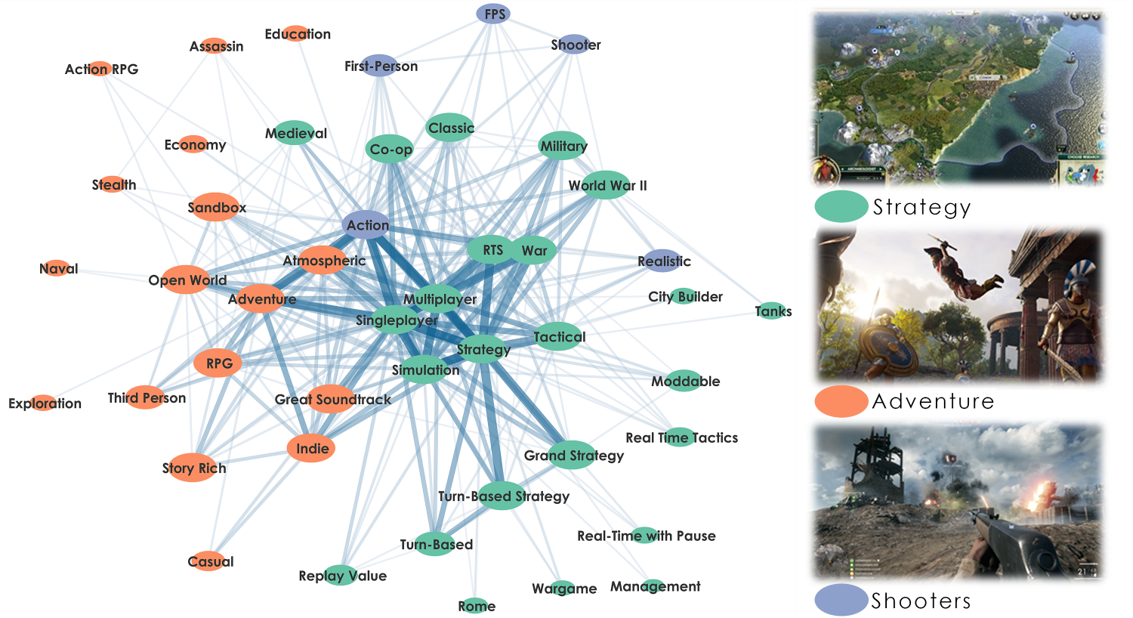

The selection of case-studies in PlayTime is based on a preparatory study I conducted: a computational analysis of the content of games tagged as ‘historical’ by millions of players on Steam, a leading, online marketplace (Figure 2; Mol 2019). The study showed how ‘historical games’ have many overlapping aspects, but can also be divided into three types. Understanding past-play in general requires us to study where different modes of play connect and diverge (Chapman 2016). This is why three games of each of these types will form the basis for comparison across all subprojects of PlayTime:

- Strategy games, including Sid Meier’s Civilization and Old World, in which you lead a historic civilization to dominate over all others (see Mol et al. 2017a);

- Adventure games, including the Assassin’s Creed series and Where The Water Tastes Like Wine (WTWTLW), in which you relive the past through expertly crafted and immersive game worlds (see Politopoulos et al. 2019b);

- (First-Person-)Shooters, including the Battlefield series and Verdun, set in the major battlefields of the 20th century viewed by players through the eyes of the character they control (see van den Heede 2020).

Figure 2: A typology using data from Steam and a network approach (Mol 2019). Nodes represent game elements tagged by the players of these games. Link width shows how frequently elements co-occur across games.

To further prepare for PlayTime, I am undertaking a pilot-project until March 2022: the Past-at-Play Lab (funded by the Leiden University Fund) in collaboration with Prof. dr. Lammes. The Past-at-Play-Lab is an outreach project in which ancient games and contemporary video games are played with members of the public, in controlled environments set up to study their play experiences. The pilot-project undertakes games user research, surveys, interviews, and auto-ethnographies and thus serves as a methodological testing ground.

Originality and Innovation

PlayTime aims to provide structure to and consolidate a rapidly growing but still amorphous body of research into past-play. It will do so by transforming current research on videogames and the past through concept, methodology, and data.

Concept

The current body of research on past and play is still divided along disciplinary boundaries. PlayTime therefore seeks to answer a question that is fundamental and new: how can we understand the past in video games as an experienced artefact (rather than as ‘new media’ forms of history, archaeology, or heritage)? The innovation here is creating an interdisciplinary framework for research on past-play that can still be rooted in the disciplines from which it arose — in PlayTime these roots lie in heritage studies’ central focus on the scholarly and public re-creation of the past in the present. At the same time, PlayTime situates itself explicitly as a subfield of game studies and development. The evolution of the MDA-model to study past-play is thus both original and innovative: it frames games as artefacts of the past and present and links academic research on the past explicitly to game development theory and method, something that is still largely unexplored (Champion 2010; Copplestone 2017; Hiriart 2019).

Methodology

PlayTime expands the limited toolsets currently used to study (past-)play with Digital Humanities and information science tools (paratext-mining and ontologies), games user research, as well as auto-ethnography, surveys, and interviews (game development and heritage game studies methods). These methodologies have never been used in conjunction before — in the study of past-play or in other game studies — and significantly reforms the original MDA-framework with a new, synthetic methodological framework.

Data

PlayTime importantly will also generate a large body of original and complementary research data on nine games that are representative of current forms of past-play. At the moment, the most comprehensive and structured data-sets available are based on evaluative studies of history and heritage ‘edutainment’. It is challenging to form a coherent view of past-play based on the data from these studies: participant numbers are low, evaluation methods are idiosyncratic, and — in contrast to most popular games — serious games are designed with a primarily educational purpose in mind (Koutsabasis 2017). FAIR data-set production should be a goal of most research projects, but the production and sharing of baseline data on these games and their players in and through PlayTime is a much-needed innovation in itself — and of crucial value to heritage studies in particular (Champion 2014).

Societal Impact

The past and play each represent highly affective and engaging subjects, and their combination in past-play has enormous potential to positively affect society. PlayTime will directly contribute to this. In fact, the design of this research project rests greatly on my interest and innovation in Open Science and Science Communication. This, and my network straddling the game community and industry and heritage field, means PlayTime will gather and share actionable insights in direct interactions with citizen players, game makers, and ‘stewards of the past’.

Citizen Players

Compared to most other media providing access to the past, games have an enormous reach. What is more, these persuasive experiences directly shape our views on the past — e.g. a recent survey I undertook showed that 90% of respondents (n=1676) believed that video games can change a person’s viewpoint on a historical event. Whether you agree with this development or not, video games have tremendous potential, both in a quantitative and qualitative sense, to shape our engagement with the past. In direct interactions, PlayTime will build on a shared passion for games to enter into conversations with citizen players about how we deal with the past in the present, including but not limited to discussions on the heritages of war and colonialism.

PlayTime will reach out to citizens, and particularly citizen players interested in the past, with:

- A project website with a section aimed specifically at citizen players, featuring game reviews, news, and popular scientific videos (a VALUE website of which I am editor in chief currently draws 3000 page views/month)

- PlayTime will organize and sponsor two game jams (creative contests in which participants make prototype games). Proto-type games made will be available for download and playable during an exhibit at Leiden University (a similar event VALUE organized drew nearly 2.000 visitors in one month).

- Weekly live-streams on Twitch will provide a direct means to converse with citizens about games and the past, as well as share project insights about how such past-play works (my current live-streaming activities have reached more than 25.000 viewers globally).

- PlayTime will share results in (inter)national news media and game journalism outlets, such as Kotaku or Eurogamer (my recent outputs in national news media such as nl and Volkskrant have reached 2-3 million people).

Game Makers

The making of games is a 200-billion-dollar annual business. When it comes to the potential for innovation, most bigger companies prefer to ‘play it safe’, letting market research and still predominantly white, male executives lead game development. One result of this is that video games end up re-telling conservative and Western ‘grand narratives’, often in a terribly persuasive way (see e.g. Lammes 2005; Loban and Apperley 2019; Mol et al. 2017a). Bigger companies are only slowly coming to terms with the fact that their games are as much entertainment products as they are institutions shaping and shaped by the cultural politics of past and present (Mol 2020). Fortunately, smaller game studios and independent creators are already active to create commercially viable games that are also diverse and knowledge-driven forms of engagement with the past.

PlayTime seeks to contribute to their forward-thinking, bottom-up initiative in a number of ways:

- PlayTime’s advisory board contains three indie game developers. Knowledge will not only be shared between these game makers and project members, but through their professional networks PlayTime will directly reach others looking for research-driven innovations on past-play.

- The jams (see above) will be open to all, but explicitly target Dutch game development students and brings these together with ‘stewards of the past’ (see below).

- We will publish a white paper for the game industry, highlighting project results and including actionable recommendations for more diverse and inclusive games based on the past.

- Project results will not only be presented at academic venues, but also at game development events, such as Games for Good and the Game Developer Conference.

Stewards of the Past

Since the 1964 Sumerian Game experiment, ‘stewards of the past’ (local and national heritage organizations, such as museums and archives, as well as individual scholars, educators and other professionals who see it as their primary role to care for and provide access to the past) have understood that computers hold the key to tell evocative histories of local and global heritages (Champion 2010). Especially in the last decade there has been a growing interest in video games by museums, educators, scholars and others. However, based on my experience working with Dutch, German, Belgium, and British heritage organizations through VALUE, it is clear that stewards of the past would like to tap into this potential of digital play but have trouble figuring out by themselves how this entertainment medium fits their primary mission. In short, expertise on video games is missing in this field, connections are missing between these organizations and the game industry, and resources are lacking to develop these things.

PlayTime seeks to bring the results of its research directly to this stakeholder group in the following ways:

- PlayTime’s advisory board contains two heritage experts, who will advise on and monitor PlayTime impact and further augment access to stakeholder networks.

- In the game jams (see above), stewards of the past will collaborate with young game makers.

- We will publish a white paper for stewards of the past, highlighting project results and including actionable recommendations on how to incorporate games in knowledge-driven activities.

- Project results will not only be presented at academic venues, but also with the (inter)national heritage sector, such as at de Reuvensdagen and ICOMOS events.

References

Apperley, T. (2006). Virtual Unaustralia: Videogames and Australia’s Colonial History. In P. Magee (Ed.). The Unaustralia Papers: the electronic refereed conference proceedings of the Cultural Studies Association of Australasia Conference.

— (2011). Gaming rhythms: Play and counterplay from the situated to the global. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures.

— (2018). Counterfactual communities: Strategy games, paratexts and the player’s experience of history. Open library of humanities, 4, 1-22.

Aycock, J. (2016). Retrogame Archeology: Exploring old computer games. NewYork: Springer.

Boler, M., & Davis, E. (Eds.) (2020). Affective Politics of Digital Media: Propaganda by Other Means. London: Routledge.

Carr, D. (2007). The Trouble with Civilization. In B. Atkins & T. Krzywinska (Eds.), Videogame, Player, Text (pp. 222–236). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Champion, E. (2010). Playing with the Past (pp. 129-155). London: Springer.

— (2014). History and Cultural Heritage in Virtual Environments. In M. Grimshaw (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Virtuality (pp. 269-283). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

— (2020). Games People Dig: Are They Archaeological Experiences, Systems or Arguments? In S. Hageneuer (Ed.) Communicating the Past in the Digital Age (pp. 13-26). London: Ubiquity Press.

Chapman, A. (2016). Digital Games as History: How videogames represent the past and offer access to historical practice. Routledge.

Chapman, A., Foka A. & Westin, J. (2017). Introduction: What is historical game studies? Rethinking History, 21:3, 358-371

Copplestone, T. J. (2017). But That’s Not Accurate: the differing perceptions of accuracy in cultural-heritage videogames between creators, consumers and critics. Rethinking History, 21(3), 415-438.

Dennis, L. M. (2019). Archaeological Ethics, Video-games, and Digital Archaeology: A qualitative study on impacts and intersections (Doctoral dissertation, University of York).

de Smale, S. (2019). Ludic Memory Networks: Following translations and circulations of war memory in digital popular culture (Doctoral dissertation, Utrecht University).

Doerr, M. (2003). The CIDOC Conceptual Reference Module: An ontological approach to semantic interoperability of metadata. AI magazine, 24(3), 75-75.

Drachen, A., Mirza-Babaei, P., & Nacke, L. E. (Eds.). (2018). Games User Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dyer-Witheford, N., & dePeuter, G. (2009). Games of Empire: Global capitalism and video games. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ellis, C., Adams, T. E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011). Autoethnography: an overview. Historical social research/Historische sozialforschung 36, 279-290

Hiriart, J. F. V. (2019), Gaming the Past: Designing and using digital games as historical learning contexts. PhD thesis, University of Salford.

Holtorf, C. (2010). Meta-stories of Archaeology. World archaeology, 42(3), 381-393.

Graham, S. (2020). An Enchantment of Digital Archaeology: Raising the Dead with Agent-Based Models, Archaeogaming and Artificial Intelligence. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Graham, S., Miligan, I., & Weingart, S (2022). Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope. themacroscope.org/2.0/.

Gruber, T. R. (1993). A Translation Approach to Portable Ontology Specifications. Knowledge Acquisition, 5(2), 199-220.

Huizinga, J. (1938). Homo Ludens: Proeve Eener Bepaling Van Het Spel-Element Der Cultuur. Haarlem: Tjeenk Willink.

Hoskins, A. (Ed.). (2018). Digital Memory Studies: Media pasts in transition. New York: Routledge.

Houghton, R. (2018). World, Structure and Play: A Framework for games as historical research outputs, tools, and processes. Práticas da História, 7, 11-43.

Hunicke, R., LeBlanc, M., & Zubek, R. (2004). MDA: A formal approach to game design and game research. In Proceedings of the AAAI Workshop on Challenges in Game AI (Vol. 4, No. 1, p. 1722).

Isbister, K. (2016). How Games Move Us: Emotion by design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jones, C. E., Theodosis, S., & Lykourentzou, I. (2019). The Enthusiast, the Interested, the Sceptic, and the Cynic: Understanding User Experience and Perceived Value in Location-Based Cultural Heritage Games Through Qualitative and Sentiment Analysis. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage (JOCCH), 12(1), 1-26.

Kajda, K., Marx, A., Wright, H., Richards, J., Marciniak, A., Rossenbach, K., . . . Frase, I. (2018). Archaeology, Heritage, and Social Value: Public Perspectives on European Archaeology. European Journal of Archaeology, 21(1), 96-117.

Katifori, A. Roussou, M., Perry, S., Drettakis, G., Vizcay, S. & Philip, J. (2018). The EMOTIVE Project – Emotive virtual cultural experiences through personalized storytelling. In EuroMed 2018, International Conference on Cultural Heritage. Lemessos, Cyprus. vcg.isti.cnr.it/Publications/2018/%20RPCMPDV18/paper2.pdf

Kee, K. (2014). Pastplay: Teaching and learning history with technology (p. 347). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Keogh, B. (2018). A Play of Bodies: How we perceive videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Koutsabasis, P. (2017). Empirical Evaluations of Interactive Systems in Cultural Heritage: A review. International Journal of Computational Methods in Heritage Science (IJCMHS), 1(1), 100-122.

Lammes, S. (2005). On the Border: Pleasure of exploration and colonial mastery in Civilization III play the world. Proceedings of the 2003 DIGRA Conference 2: 10.

LaPensée, E. (2020). When Rivers Were Trails: cultural expression in an indigenous video game. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 1-15. doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1746919

Lee R.S.T. (2020) Natural Language Processing. In: Artificial Intelligence in Daily Life. Springer, Singapore. doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7695-9_6

Loban, R. & Apperley, T. (2019). Eurocentric Values at Play: Modding the Colonial from the Indigenous Perspective. In P. Penix-Tadsen (Ed.) Video Games and the Global South (87-100). Pittsburgh: ETC Press.

McCall, J. (2013). Gaming the past: Using video games to teach secondary history. London: Routledge.

— (2020). The Historical Problem Space Framework: Games as a Historical Medium. Game Studies, 20(3).

McCallum-Steward, E. (2008). ‘A Biplane in Gnomeregan’: Popular Culture, Digital Games and the First World War. In M. Howard (Ed.) A Part of History: Aspects of the British Experience of the First World War (pp. 190-208). London: Bloomsbury.

Mol, A. A.A., Politopoulos, A., & Ariese-Vandemeulebroucke, C. E. (2017a). “From the Stone Age to the Information Age”: History and Heritage in Sid Meier’s Civilization VI. Advances in Archaeological Practice, 5(2), 214-219.

Mol, A. A. A., Ariese-Vandemeulebroucke, C. E., Boom, K., & Politopoulos, A. (Eds.). (2017b). The Interactive Past: Archaeology, Heritage & Video Games. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Mol, A. A. A. (2014). Play-things and the Origins of Online Networks: Virtual material culture in multiplayer games. Archaeological Review from Cambridge, 14(1): 144–166

— (2019). Gaming Genres: Using Crowd-Sourced Tags to Explore Family Resemblances in Steam Games. Paper presented at DH2019, Utrecht (8-12 July 2019), dev.clariah.nl/files/dh2019/boa/0946.html.

— (2020). Toying with History: Counterplay, Counterfactuals, and the Control of the Past. In M. Korber & F. Zimmermann (Eds.), History in Games: Contingencies of an Authentic Past. Bleinfeld: Transcript Verlag.

Morgan, C. L. (2009). (Re) building Çatalhöyük: Changing virtual reality in archeology. Archaeologies, 5(3), 468.

— (2019). Avatars, Monsters, and Machines: A cyborg archaeology. European Journal of Archaeology, 22(3), 324-337.

Munslow, A. (2019). The Aesthetics of History. London: Routledge.

Nikolenko, S. I., Koltcov, S., & Koltsova, O. (2017). Topic Modelling for Qualitative studies. Journal of Information Science, 43(1), 88-102.

Perkins, J. (2014). Python 3 text processing with NLTK 2.0 cookbook. Birmingham: Packt Publishing Ltd.

Pfister, E. & Zimmermann, F. (2020). Erinneringskultur. In O. Zimmermann & F. Falk (Eds.) Handbuch Gameskultur (pp.110-116). Berlin: Deutscher Kulturrat.

Politopoulos, A., Ariese, C., Boom, K., & Mol, A. A. A. (2019a). Romans and rollercoasters: Scholarship in the digital playground. Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, 2(1),163–175.

Politopoulos, A., Mol, A. A.A,, Boom, K. H., & Ariese, C. E. (2019b). “History Is Our Playground”: Action and Authenticity in Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey. Advances in Archaeological Practice, 7(3), 317-323.

Reinhard, A. (2018). Archaeogaming: An introduction to archaeology in and of video games. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Rollinger, C. (Ed.). (2020). Classical Antiquity in Video Games: Playing with the Ancient World. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Ryan, M. L. (2001). Narrative as virtual reality: Immersion and Interactivity in Literature. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Salen, K., Tekinbaş, K. S., & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of play: Game design fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT press.

Sharp, J., & Thomas, D. (2019). Fun, Taste, & Games: An Aesthetics of the Idle, Unproductive, and Otherwise Playful. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Shelley, J. (2017). The Concept of the Aesthetic. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta, plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/aesthetic-concept/ .

Smith, D.W. (2018). Phenomenology. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta, plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/phenomenology/

Squire, K. (2004). Sid Meier’s civilization III. Simulation and Gaming, 35(1), 135-140.

Uricchio, W. (2005). Simulation, History, and Computer Games. In J.Raessens & J. Goldstein (Eds.), Handbook of Computer Games Studies (pp. 327-338). Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

van den Heede, P.J.B.J. (2020). ‘Experience the Second World War Like Never Nefore!’: Game paratextuality between transnational branding and informal learning. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 43 (3), 606-651. doi: 10.1080/02103702.2020.1771964

Whalen, Z., & Taylor, L. N. (2008). Playing the Past: History and Nostalgia in Video Games. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Wing, R. L. (1966). Two computer-based Economics Games for Sixth Graders. American Behavioral Scientist, 10(3), 31-35.

Wright, E. (2018). On the Promotional Context of Historical Video Games. Rethinking History, 22(4), 598-608.

Zagal, J. P., Mateas, M., Fernández-Vara, C., Hochhalter, B., & Lichti, N. (2007). Towards an Ontological Language for Game Analysis. In S. de Castell & J. Jenson (Eds.), Worlds in play: International perspectives on digital games research (pp. 21-35). New York: Peter Lang.